Jesus, Copyright, and the Art of Collage:

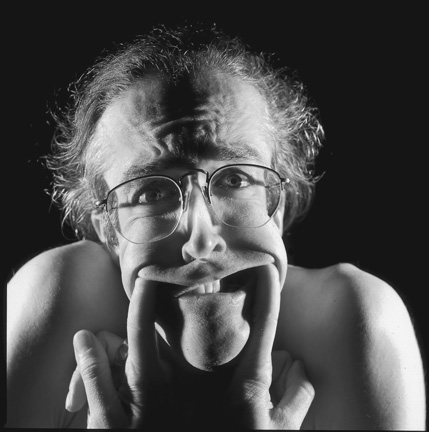

An Interview with Mark Hosler of Negativlandby Jon Nelson

If you've ever downloaded a song off the internet, noticed snippets of phone calls or presidential speeches spliced into music, or even just thought about the knottiness of copyright law, you've got Mark Hosler and Negativland, at least in part, to thank.

If you've ever downloaded a song off the internet, noticed snippets of phone calls or presidential speeches spliced into music, or even just thought about the knottiness of copyright law, you've got Mark Hosler and Negativland, at least in part, to thank.Negativland has been a subversive force in college and alternative radio for more than twenty-five years now, and their manic, cerebral brand of unauthorized sampling has also made the occasional brush with the mainstream - creating an uproar (and a few red-faced media outlets) with a fake press release blaming their "Christianity is Stupid" single for an axe murder, and being sued by Ireland's biggest rock band, among other notable moments.

The band - more accurately, the Negativland collective, which does everything from standard albums to a radio show, video collages, books, lectures and Web pranks - had its genesis in Hosler's high-school experiments with found sound and tape-splicing. "[Frankenstein] was sort of a central mythological, metaphorical story for me as a kid, and I ended up doing collage," as he recalls. "To this day I have always enjoyed finding things that exist and finding ways to repurpose them and reuse them."

Initially working on his own in Bay Area suburbia, Hosler found a group of kindred spirits who in 1980 released their first record as Negativland. Over their next few records, the collective honed its signature mélange of sounds, which Hosler defines as "a mixture of noise, electronics, experimentation, sound [and] media, all combined with a sort of pop sensibility - a sense of songs, a sense of melody, something weirdly acceptable and engaging. It's accessible experimental music for people with attention deficit disorder."

1987's Escape From Noise, released on California punk label SST, brought them to a wider audience; the subsequent Helter Stupid (a response to the "Christianity" flap) found Negativland establishing their political ethos more firmly.

And then there was "U2." The two-song single could have been just another cult hit for the band - except its cover art featured the song title in huge red figures. And it happened to come out in 1991, just as anticipation was reaching a fever pitch for Achtung Baby, U2's follow-up to the zillion-selling Joshua Tree and Rattle and Hum. A protracted, costly lawsuit and a split with SST eventually resulted - as did the band's increasingly resolute commitment to irreverence and questioning. (Like all of Negativland's best work, incidentally, the single is riotously funny: it's a virtual beat-by-beat deconstruction of "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For," overlaid with a decidedly unauthorized vocal track of wholesome America's Top Forty DJ Casey Kasem ranting profanely about everything under the pop-music sun.)

Since the "U2" flap, Negativland has gone largely back under the radar, expanding their roles further into radio and video, finding a welcome home for their work on the Web, and even lecturing across the country on copyright and intellectual property issues. They do still find time to release the occasional record - "we should be in the Guinness Book of World Records for most concept albums ever made," as Hosler says - and have recently been working with the public-domain-awareness group Creative Commons to create new, more sampling-friendly music and video licensing.

And even with all that, Mark Hosler found time to sit down with our Jon Nelson to discuss copyright, collage, and Negativland's newfound Jesus fixation.

Jon Nelson: You've sort of been forced into this position of authority on issues of copyright and creativity -- how has your position on fair use developed over the years?

Mark Hosler: Copyright law is frequently misunderstood. Copyright is not an all-encompassing property right. It's a balancing act. If you read copyright law, it's written that way. The law recognizes that you want to allow people who create things to own and control and profit from their work on the one hand; on the other hand, the law also recognizes that there's no such thing as a truly new idea. You build on what came before you. You're influenced, you appropriate, you steal, you borrow - use whatever term you like - but there's no such thing as an original idea. That's something people need to get over. So, yes, you should profit from your work, but how much and to what degree? There's a limit. Should the estate of William Shakespeare be able to sue the guy who wrote West Side Story because he stole the storyline from Romeo and Juliet? Should the guy who came up with the English drinking song that ended up being the melody of our national anthem be able to sue Francis Scott Key? It's ridiculous when you start to think about it. Think about how many ads now use images by Vincent Van Gogh. How long do you need to control these things?

In the case of Negativland, we're not bootlegging or pirating entire works. We're using a chunk of something, and we're combining it with chunks of hundreds of other things. It's collage. My feeling is, if you want to completely, utterly control your work if you're a creative person, you should just keep it in your bedroom and play it for your mom and dad and your friends. But if you're going to put your work out there into the world, into the literal public domain, then I think that part of the cultural bargain you make is that you don't deserve and you don't get total control. It's a particularly ugly, corporate way of thinking, small-minded and short-sighted, to just say, "Mine! Mine, mine, mine, mine, mine!" It's culturally stingy to take such a position. If you take that kind of corporate-think, about the control and ownership of everything in the cultural realm, to its logical conclusion, it's the death of art. If all of culture is privately owned and controlled that leaves us nothing to do but sit passively and consume it. That's just darn silly.

There's this old idea among activists, that one thing you can do is to try and change the world; another thing you can do, though, is to live your life as if the world already is the way you want it to be. That's one of the ways Negativland chooses to make art and music. We're not so much setting out to break these laws and rules as we are trying to ignore them altogether - to behave as if they don't even exist and just follow the creative impulse and try to make something interesting.

It's exciting to see that some of these ideas that we've been talking about for years are getting into the mainstream. It's not so radical anymore. It's more like we're kooky elder spokespeople, the old guys.

JN: How do you think the mainstream's been affected by your work?

MH: Well, the landscape has changed dramatically. When Negativland was sued in '91, we correctly realized that we were like the canary in the coal mine. That these issues about who owns the culture, what is property when you're in the digital world, are going to become huge in the next decade. This is the tip of the iceberg. And we realized that the issues we were dealing with were much, much greater than just the trials and tribulations of one little experimental noise band. That's one reason we thought we needed to speak out. And because we were being sued on behalf of the world's largest rock band - at the time U2 was at their peak, they were huge - we realized we had a kind of platform. We could take this and use it as an opportunity to do something, we hoped, responsible and start a public discussion about these things.

So, fast forward a decade later, Napster happens. DSL, cable modems, incredibly fast computers, file sharing - these issues explode into public consciousness. Books come out like The Future of Ideas by Lawrence Lessig [and] Copyrights and Copywrongs by Siva Vaidhyanathan. These guys are both articulate, they're respectable, they're college professors, they're getting on CNN - and they're agreeing with what we've been saying all along. [Now] people are patenting seeds, people are saying they own your DNA, individuals are copyrighting things in the natural world, and it has some very disturbing implications.

When I encounter people who think that our point of view is wrong or ridiculous, or who think we're just thieves - the world is not so simple. All throughout human history people have made art, they've made music, they've made culture that reacts to the world they live in. What else could you possibly react to? You might want to make a painting of a field of flowers. Except now, that field of flowers has been turned into a Wal-Mart. So maybe, I might want to make a painting of a Wal-Mart. But I also have other technology, so maybe I want to take a photograph of the Wal-Mart. Maybe a digital photograph. And the computer allows me to do things to that image. Or maybe I want to take a recording of a Wal-Mart ad. There are so many ways you can capture bits and pieces of the world around you. The creative human impulse is the same as it's always been, we just live in a different world. We live in a world of media information, advertising, music - a constant barrage of stuff. And we also have different tools. Instead of paintbrushes, clay, our fingers, there are all these other ways to capture and copy things that exist. And the computer ends up being the ultimate cut and paste collage box. It's very easy to do that on a computer - the technology almost encourages it. [With] the channel-changing, fast spliced, fast edit world that we live in, with all these strange juxtapositions of things bumping up against each other, it seems inevitable to me that some people in the arts would react to that world and make stuff. It's just the most natural thing in the world for me to say, "Hey, let's add in this recording of our parents cooking in the kitchen, and the dog's barking out in the yard, and the TV set's on - we'll just mix it all in." It was just our environment. The years went by, and we started getting more and more critical of that environment, the media environment particularly, and what we were using in our music and how. [And now,] you know, we're actually weirdly respectable. I get asked to do talks in prestigious universities (laughs).

JN: (laughs) That must be nice.

MH: Maybe it'll give you some hope. I mean, we've just been doing this crazy-ass, cut-up collage for all this time, and I'm trying to convey a sense, when I talk to these people in the more academic world, of questions [like] "Why is this fun? What is the appeal? What is the creative impulse that drives people to make stuff like this? Where does it come from? Forget about what the law says. . ."

JN: You can tell that some people just want sound collage artists to stop making what they're making. Fine, you can stop all these artists from making it. Maybe in general, it's not that big of a deal. But what more are you also stopping? What might those collage artists have inspired? You're stopping a whole process of influence sharing, you're stopping a part of cultural evolution.

MH: Exactly. The reason that Negativland came to the kind of attention that it did was because around the same time, [with] hip-hop and rap, you had this whole genre of music based on sound collage that was beginning to make lots of money. For the decade before we were sued, no one cared about people doing audio collage. But rap and hip-hop became this audio collage form that started making millions and millions of dollars. That's when a lot of unscrupulous types started to step in, sniffing around for money. So when those first lawsuits were filed against De La Soul and Biz Markie, it had a real chilling effect on the whole evolution of hip-hop and rap. Public Enemy's Chuck D was really the only one to step forward, to recognize this as a kind of cultural oppression. It wasn't just about [the original artists] getting paid for the samples used, but it badly effected the evolution of that whole art form. I was amazed that more musicians from rap and hip-hop weren't outraged.

But the landscape has really shifted. Our point of view is really not seen as so radical anymore at all. You have only to look at things like mash-ups, which are a really interesting phenomenon to me - I couldn't imagine that sound collage could get any more mainstream, and then it took this quantum leap. Thousands of kids in England were taking two or three pop songs and layering them on top of each other, trying out fun combinations. And they weren't trying to critique the media, there was no comment about the music implied, nothing political. It was just fun. The criteria for the kids were just: is it fun to dance to?

And it's evolving too. You can tell, with the people getting into it, their work [is] getting more complex. They're starting to cut stuff up. They're running more than just two songs together, starting to mess around more, altering the sound, time-stretching it. Before you know it, someone who's really serious about these mash-ups is going to morph into more and more original, more manipulated kind of thing.

Jon Nelson: Your first three major releases were on SST; did you guys think of yourselves as a punk band?

Mark Hosler: I don't think we were ever identified as a punk band, but once that word got out, people noticed us because [our early album] covers were handmade, one of a kind - we'd inadvertently created a great marketing tool. People would see a few in the store and pick one up and say "What the hell is this?" And someone else in the store might say "That's the weirdest damned thing you'll ever hear. Don't know what I think of it, but check it out." Which is what we wanted. We were trying to make something incredibly strange, different, that didn't sound like anything any of us had ever heard.

So I think Negativland is pretty punk rock in terms of our attitude - and for me punk rock was, when it started out, not a sound or a look or a fashion or a style, it was a point of view. It was about not following the rules, about making things on your own, about do-it-yourself culture. It was about making something with very little - you take next to nothing, no resources, and you manage to do something. And it was about doing things that were provocative.

When it turned into just a style of music and of fashion, I was very disappointed. But I thought, creatively, our music is lots more radical than this kind of pedestrian, punk, rock 'n roll stuff, and we look kind of normal, and, look, we come from the suburbs. And we ended up wearing that as a badge of honor. I really think my sense of the spirit of it is something we've tried to stick to, especially with the "U2" single. I was [only] interested in being "extreme" in my head, in what I created.

JN: What would your response be to those who criticize the band, pointing to the various media stunts and whatnot?

MH: I think the music should be judged on its own merits. I mean, it's fine that we've gotten that kind of attention over the years, it's great, but I really think that if all we were trying to do was provoke people and stir things up, we wouldn't spend three years working on a record. When you actually listen to the work, it's pretty clear that we work very, very hard on what we do. We really are trying to do something very interesting with sound; we aren't sitting around trying to think of ways to upset people or cause trouble.

When we have caused trouble, they were experiments, in the same way that we experiment with sound - what happens if I plug this into that, what happens if I turn this tape backwards? There's a sense of questioning, wondering "what if?" In the same vein, [we've wondered] "What happens if we put out a press release that's a lie?" "What happens if we make a record that pretends to be a record by the biggest rock band on the planet, but it really is a record by Negativland?" I can look at what we've done over the years, and every aspect, every level of our work, is asking questions about "what if I do this?" and "what if we try that?"

It happened that this kind of work extended beyond just making sound - we were doing radio performance, we were doing films, photography, we did design work. When we do shows, I get to come up with set ideas, costumes. Negativland was always supposed to be an umbrella under which we could create anything we wanted. Now we're writing, we're publishing, we do lectures. We're set to put out a DVD in 2005 - a collection of film work that no one's ever seen, that we've been working on for six years.

For me, the hoaxes and pranks, the prodding of the media, made perfect sense - it was all part of the work. And we had no idea it would have the big results it did. We were a lot more naive than people think. We're not so naive now, but we learned by doing it. Why do I know so much about copyright now? It's not because I set out to take this on, it's because our works encountered these types of laws, we were smashed because of it, and we were forced to have to understand copyright laws and the ways corporations work. We realized what was wrong and it compelled us to speak out about it.

JN: With all this going on, then, what's Negativland up to? Tell me more about the Mashin' of the Christ project.

MH: [Using DCSS DVD - ripping software] we took every scene, from every Jesus movie ever made, of Jesus has been beaten, whipped, flogged, abused, punished, knocked down, [and] slapped around, and created this whole montage. And we purposely edited it like a dumb early '80s rock video, where all the edits are on the beat. It's got a sort of stupid quality to how it's edited that I think is hilarious.

We watched every Jesus movie ever made, in order to create the video. [And what we noticed is] that each film relates to the time period it's coming out in, as either a reflection of it or an expression of it in some way. I thought, what does it mean that the most popular Jesus biopic ever made, that came out in 2004, happens to be the most violent, most brutal, most disgusting, intense, over-the-top version ever? I don't know the answer, but I wonder what it says about where we're at now in terms of our tolerance for violence and brutality.

It's interesting that it comes out at a time when many, many Americans are just quietly allowing our tax dollars to destroy Iraq, to hold people in detention cells in Guantanamo. We're allowing some very, very terrible things to be done in our name. I think history's going to look back on this period, and we're going to look very bad. Because we just didn't do anything.

JN: And what's happening next?

MH: No Business is a book/CD project, and that's coming out in early 2005. In it, Negativland will be going back into the very subject matter we've been discussing: copyright, intellectual property issues. We haven't actually issued any work related to this since our Fair Use book came out in 1995. People often seem to think that all of our work revolves around this, but it doesn't - we've had lots of projects that continue to appropriate bits of things, but that don't really address the legal, cultural issue of copyright. Most of our other work is a mixture of appropriated work and original music mixed with things that we've found. What's unusual about this new record, No Business, is that 100 percent of is reused, re-purposed, recycled material. And it's pretty damn funny. Especially following Deathsentences [of the Polished and Structurally Weak], which was our last big [book/CD] project - pretty damn not funny. We're in the midst of reissuing Helter Stupid, the project about the axe murderer hoax. That's coming out next month. And finally, we have a DVD that we've been working on for many, many years. That's going to come along with a bonus CD, which, if you know our work well, is going to really surprise you.

Jon Nelson is an artist, curator and producer focused on sound collage. His nationally syndicated radio program, Some Assembly Required, is a weekly radio show, featuring the talents of audio artists who appropriate sounds from their media environments.

Read this article in its original context:

Page One

Page Two

You can also read this article at ruminator.com